Lectionary: Proper 8(C)

Text: Luke 9:51-62

Sermon

After Jesus provided food for more than five thousand people, expectation of a conquering Messiah was high. But instead of announcing a conquering kingdom, Jesus told his disciples that he would suffer and be killed. He said to them, “If any wish to come after me, let them deny themselves and take up their cross daily and follow me. 24 For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will save it. 25 For what does it profit them if they gain the whole world but lose or forfeit themselves?” (Luke 9:23-25 NRSVue)Following this Peter, James, and John accompanied Jesus where

he was transfigured atop a mountain and where Moses and Elijah appeared next to

Jesus. They heard a voice from a cloud speak to them saying, “This is my Son,

my Chosen, listen to him.” (Luke 9:35b)

These events provide key narrative contexts through which

today’s gospel reading can be interpreted. “Whose words and actions do we

follow?” and “What does following Jesus mean?” are the implied questions

beneath what we heard.

From a literary perspective, the reading today contains strong

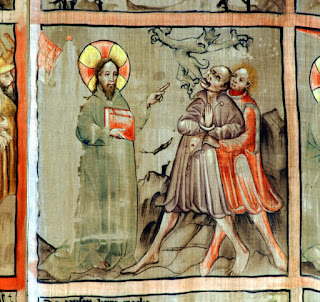

echoes and allusions to several stories concerning the last days of Elijah and

the call of Elisha.[1]

2 Kings 2:1 begins, “Now when the LORD was about to take

Elijah up to heaven…” echoing what Luke wrote, “When the days drew near for him

to be taken up…”

In 2 Kings 1, Elijah calls down fire from heaven to destroy

two groups of Samaritan messengers.

In the call of Elisha found in 1 Kings 19, Elisha is called

while plowing a field. Elisha says to Elijah, “Let me kiss my father and my

mother, then I will follow you.” Elijah gives permission for Elisha to do so.

Elijah and Elisha are two prophets who preside over a period

in Israel’s history where God works visibly and mightily to provide for and

intervene on Israel’s behalf.

Jesus’ miraculous feeding of a crowd, warnings about costs of

following him, his transfiguration, and his announcement of his imminent “being

taken up” signaled to the disciples that something big was about to happen. However,

the path and destination of Jesus would be quite different from what the

disciples hoped for and expected.

Luke 9:51 to 19:28 is the largest unit in the Lucan gospel.

It is referred to as the travel document or narrative since it

details Jesus’ movement from Galilee to where he enters Jerusalem on what we

call the Triumphal Entry. This section is Luke’s collection of events and

teachings of Jesus to future disciples about what it means to follow Jesus and

carry on the work of his gospel.

Let’s dig into today’s text more closely and see what else

we might uncover.

First point to note is that when Jesus is rejected by a

Samaritan village, he just moves on. James and John wanted to respond with

violence and vengeance, as Elijah had done in their history, but Jesus does not

permit it. Luke attributes the rejection due to Jesus having set his face

toward Jerusalem. What this means is that the Samaritans appear to have

rejected Jesus because of his convictions and what he expected to happen once

he got to Jerusalem.

Some questions for us regarding this are, how willing are we

to walk away from rejection without responding in kind or worse? Are we willing

to let go of violence and vengeance altogether as a response, even when it

challenges and threatens our core convictions? Are we willing to respect the

freedom and agency of others and not attempt to force our beliefs and ways onto

those who aren’t willing?

The next part of the reading contains three interactions.

The first and third are about an individual coming to Jesus asking to follow

him. The middle one is Jesus calling a person to follow him.

Let’s review the first interaction:

57 As they were going

along the road, someone said to him, “I will follow you wherever you go.” 58

And Jesus said to him, “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests, but

the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head.” (Luke 9:57-58)

This can be interpreted as Jesus describing some of the

privations that might be experienced because of following him. It might be Jesus

asking if this individual has counted the costs. It might be a naïve

individual, upon seeing the popularity of Jesus, wants to join the bandwagon.

But there could be more. Jesus’ reply uses the term “foxes”

and “birds of the air.” The “fox” was a symbol for Ammonites, and Jesus called

Herod Antipas “that fox.” The “birds of the air” was a phrase used to refer to

gentile nations.[2]

In a veiled fashion, Jesus may have been querying this would-be follower if he

really wanted to follow someone who was against the political and power

structures of the world. Perhaps this individual was politically connected, or

perhaps thought Jesus could be the means to it. Jesus dismantles any kind of

political and power ambitions of this person.

For us, the same question is posed. Do we see Jesus and

Christianity as a means for acquiring political power and wealth. Because if

so, we are misguided. If someone is promising that kind of influence, we should

be questioning whether the Christianity they espouse is the one of Jesus Christ

of Nazareth, or something else.

The second interaction reads as follows:

59 To another he said, “Follow me.”

But he said, “Lord, first let me go and bury my father.” 60 And

Jesus said to him, “Let the dead bury their own dead, but as for you, go and

proclaim the kingdom of God.” (Luke 9:59-60)

This has caused consternation among interpreters. On the one

hand, interpreters have taken this to be entirely metaphorical, speaking about

spiritual life and death. On the other hand, interpreters refer to a cultural

practice of multiple burying events and interpret this text as referring to a

second burial after the body has fully decomposed.

However, Levine, Brettler, and Bailey state that the

phrasing used here strongly implies that no one has died yet.[3],[4]

They explain that “Let me go and bury” is a Middle Eastern idiom used to mean

“let me go and serve my father while he is alive.” Honoring one’s parents is

part of the Ten Commandments, given by Moses. It is an important pillar in maintaining

family and community. What Jesus is telling this individual is that following

him supersedes cultural values, it supersedes even what Moses wrote down as

words received from God.

But reading between the lines, it sounds like this

individual is making excuses. He seems to want the praise and acknowledgment of

following Jesus, but on his own terms. He wants to follow Jesus only when it is

convenient.

The third interaction has some similarities to the previous.

This reads:

61 Another said, “I will

follow you, Lord, but let me first say farewell to those at my home.” 62

And Jesus said to him, “No one who puts a hand to the plow and looks back is

fit for the kingdom of God.” (Luke 9:61-62)

Whereas Elijah allowed Elisha to go back to his father and

mother and leave plowing, in this text Jesus does not. Just as Jesus is greater

than Moses, Jesus is greater than Elijah. The precedent set by Elijah in his

call to Elisha as disciple is superseded by Jesus making new and greater

demands of his disciples.

We might wonder why Jesus doesn’t even allow a quick

farewell. The problem is how a Greek word is translated and what we think that

means. The word ἀποτάξασθαι is translated “say

farewell” here but it is better translated “take leave of” (which is how this

word is translated everywhere else in the New Testament) and which can also

mean “renounce.” Kenneth Bailey writes that what this means in practice is that

the person is asking to return to his home and community and ask for permission

to leave and follow Jesus, knowing full well that the community will not.[5]

Like the second individual, the third individual expresses

performative discipleship. He wants the accolades and admiration of those who

are watching and listening, but he knows that at the end of the day, he does

not have to give up anything.

Taken together, our reading indicates several aspects of

following Jesus. It opposes power, might, wealth, violence and vengeance upon

which the world’s political, social, economic, and religious systems are built.

The way of Jesus’ gospel of peace, love, and inclusion supersedes all previous

religious and spiritual traditions. Following Jesus may mean having to renounce

community and family ties, if they are opposed to his ways. Following Jesus is

not a road to comfort, power, and wealth. It can lead to rejection,

persecution, and death.

In the three dialogues Jesus had with would-be disciples,

their response is not recorded. Luke asks his readers to place themselves — us

—in their places. How will we respond?

References

Bailey, K. E. (1976, 1980). Poet & Peasant

and Through Peasant Eyes (Combined Edition). Grand Rapids, MI: William B.

Eerdmans.

Levine, A.-J., & Brettler, M. Z. (2011, 2017). The

Jewish Annotated New Testament, 2nd ed. Oxford, NY: Oxford University

Press.

[1]

1 Kings 19:15-21; 2 Kings 1:2-16, 2:1-12.

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]