Lectionary: Proper 11

Text: Matthew 13:24-30, 36-43

Literary and Historical Contexts

These three

weeks – last week, today, and next week – the gospel texts go through the

parables that are recorded in Matthew chapter 13. One way to read them is to

take each one as an isolated parable, self-contained and interpreted within

itself. Additionally, a couple of them have interpretations that are offered:

the parable of the Sower which we heard last week, and the parable of the weeds

found in today’s reading.

But if we

zoom out and look at how this gospel writer has arranged the narratives around

chapter 13, we can find some possible reasons for this textual and literary

arrangement and perhaps some interpretive keys as well.

Chapter 12

is a series of narratives about how religious experts and even his birth family

had conflicts and misunderstandings about Jesus. Chapter 13 ends, after the

parables, with Jesus’ rejection by his hometown, Nazareth. From a historical

perspective, this could reflect what was being experienced by the community to

whom Matthew wrote. It is then, quite likely that the parables as recorded

through Matthew, addressed and offered answers to some of the questions that

may have been strong in the minds of one of the early Christian communities.

Here I want

to offer some thoughts on the interpretations that are found alongside the

parables. According to the text, it is Jesus who explains his own parables

after his disciples ask about them. And many scholars accept that these

explanations come from Jesus. But there are other scholars who question that

view. They suggest that it was the gospel writer who provided these

interpretations as coming from Jesus. Since the author of the gospel of Matthew

was separated from Jesus by four or more decades, he may have been writing down

a tradition that had become attributed to Jesus.

Some reasons

to think that the interpretation given may not be originally from Jesus include

1) that the interpretation fits too neatly, and 2) the interpretation is too

allegorical rather than parabolic. Generally, parables were told to raise

questions and to discomfort, to cause listeners to think, and offer multiple

interpretations.

Whether the

interpretations found in Matthew 13 are originally from Jesus or not ultimately

does not matter too much, except when they stop us from pondering over them for

additional meanings. The interpretations do fit with giving answers to the

historical question of why Jesus and his gospel was rejected by so many who

heard it.

With some of

the preceding literary and critical background out of the way, let us investigate

today’s text about the parable of the weeds.

Thinking About Parables

This is

another of the parables that I recall hearing in sermons and in children and

youth classes. You may have had the same kind of experience. Therefore, it is

easy to kind of skim over it, saying, “Uh huh, yup,” and content that we know

what it says. It is so familiar, as is the interpretation of it given some

verses down. We know how the parable reads and what it means. Or do we?

I began

preparation for this sermon by going through several commentaries, and of them

there were two that offered suggestions for an interpretation of the parable

that pretty much is the opposite of the interpretation given in the Matthean

text.[1]

At first, I thought this interpretation was bonkers and couldn’t see how it

could be derived from the parable’s text. But then I got into the “weeds” (so

to speak) about the weed that is the likely one described in the parable. And

from there I looked at the next two, short parables following today’s and

realized, hmm…, yes…, the alternative interpretation is completely

nontraditional and seems totally crazy, but…, not so crazy and fits

thematically and literarily where the parable is placed among the other ones.

If we take the perspective that the interpretation that is offered in the text

is not the only one or the only correct one, it opens multiple other

possibilities.

That’s the

general thought process I had. Now let’s get into some specifics.

Thinking About Weeds

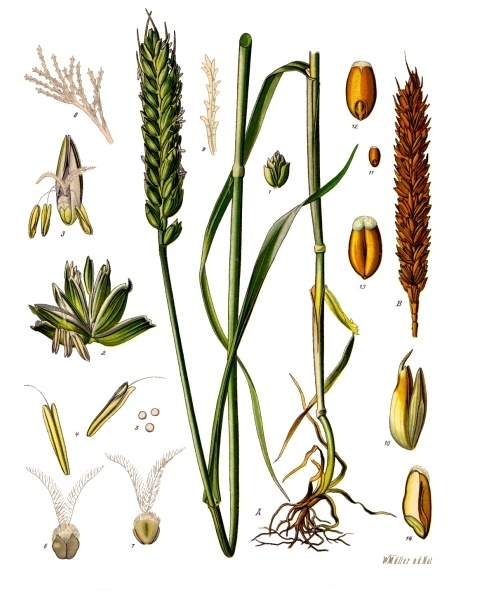

|

| Wheat |

For some

reason, perhaps because I heard this story many times growing up, and those

early impressions still are the most prominent in my mind; when I hear or read

about the weeds in this parable, I think of normal, everyday weeds most of us

are familiar with. They are still annoying, frustrating, and take work to dig

out, but that pales in comparison with the weed that is the most likely one

found in this parable.

| Bearded Darnel |

I figuratively

went into the “weeds” to learn about the weed of this parable. What most scholars

believe this weed is, is the one known as the bearded darnel. It is a

truly fascinating plant.[2]

What I found explains some of the specific details found in the parable.

For

instance, why does it take so long for the slaves to discover that there are weeds

mixed with the wheat? Because the darnel looks exactly like wheat until the

unripe stalks of fruit open up at the same time as the wheat. Then the two

plants become identifiable. And by then the roots of the wheat and weeds are so

intertwined that it is impossible to dig up the weeds without also digging up

the unripe wheat.

The sorting

could only happen after they are harvested, and the good stalks sorted out from

the darnel. The wheat stalks have a straight fruit while darnel stalks have

fruit that develops in small alternating clumps. Modern sorting machinery is

able to automatically separate the wheat, but it was previously a tedious job done

by hand.

The darnel is

a weed that has fully adapted to infiltrating cultivated wheat crops. It cannot

exist on its own. It must be planted alongside the wheat by humans. It is also

interesting to note that oat and rye were found by humans because they too, required

human cultivation. However, they were found to be useful to humans and thus

their adaptation worked out quite well.

Darnel, on

the other hand, is mostly harmful to humans. It does have properties that can

cause intoxication – dizzy, off-balance, and nauseous – in small amounts. In

larger amounts it is fatal. This small amount is known to have been

deliberately introduced into ancient and medieval brewing to obtain their

effects and increase the intoxication from drinking a beer, for instance. There

is at least one scholar who argued that because it was impossible to fully

eradicate the presence of darnel from wheat, that medieval baked goods were to

some degree, intoxicating, and therefore, “European peasantry lived in a state

of semi-permanent hallucination.”[3]

Sort of like the “special” weed brownies that we might find down the

street today.

If you ever

encounter the surname Darnell, it is quite probable that one or more of

their ancestors had cultivated the darnel plant for its properties, to be added

intentionally in brewing beverages or to baking.

Why did I

just spend a rather lengthy digression bringing you details about the bearded

darnel? Because 1) it occupies a grey area between potentially useful and

harmful; 2) it was something that was a part of the normal wheat planting

process to have some darnel just accompanying the wheat; and 3) it starts out

unnoticed but then it becomes quite obvious. Each of these three observations

can alter the allegorical interpretation that is found in the Matthew text. And

I think that ancient societies knew these things about wheat and the bearded

darnel, including the hearers of the parable.

I am taking

the interpretation suggested by the two commentators mentioned earlier, turning

upside-down the traditional interpretation. This interpretation takes the

position that the householder or the farmer represents the landowners of

society, those who hold power and privilege; those who control the political

and economic powers. The “good” seed then, is only “good” from their

perspective. They sow the good seed to maintain the status quo, with their

power and privilege, but for those who are not part of the upper class, the

good seed is bad, for it means continued poverty and injustice. One of the

commentators mentioned earlier writes,

“On the other hand, perhaps the field in this parable is a

metaphor not for the church as much as for the world. The farmer then might

stand not for God but for the prevailing social and economic structures of

Jesus’ day, even the Roman Empire itself, and the ‘enemy’ is instead Jesus,

whose preaching, teaching and healing are God’s invasion of the old world with

the empire of heaven. If so, Jesus is here, as in the Beelzebul controversy,

the one who is stronger than Satan and ties him up in order to plunder his

house (12:29), and the farmer represents the social, political, and economic

forces that oppress God’s people. Although the world opposes the church, it

will not be destroyed. God will save it and judge its enemies.”[4]

The second

commentator adds another facet to this interpretive perspective, writing,

“Individual Christians are sown as subversive ‘weeds’ in that field.”[5]

I mentioned

earlier that I thought this interpretation was crazy and untenable, but as I

read through the parable with the information about the darnel weed in mind, it

became more plausible.

The first

place that raised a question for me was when the householder says that “an

enemy has done this.” Although the hearers, as an outside observer, know this

based on what has already been described, on what basis does the householder

claim this? If the weeds were a normal, if undesired part, of all wheat fields,

how could the householder claim that an enemy has intentionally planted the

weeds? In my mind this opened the possibility that a simplistic, straightforward

allegorical interpretation, while permissible, may not be the only one

available.

And then I

read the next two short parables (which is part of next week’s gospel reading).

The first parable is about a mustard seed, where a tiny seed mysteriously grows

into a large shrub that allows birds to nest in it, becoming an integral part

of the ecosystem. The second parable is about yeast that is added to dough,

mysteriously grows and permeates the entire dough and becomes an inseparable

part of it.

Both

parables share themes of mysterious origins, growth, and becoming integrated

into its environment. And then I realized that the same themes could be found

in the parable of the weeds: the sowing that happens in secret, the mysterious

growth, the reveal of the extent of the growth that isn’t apparent until close

to the end, how it becomes inextricably intertwined with the environment, and

the confounding of the entire process – these are all themes in the parable of

the weeds that are shared with the next two parables.

And it was

at this point that I became convinced that a very different, upside-down

interpretation is quite plausible and can be supported by the literary context:

where perhaps “good” may sometimes be merely a label that is given to something

that is used to justify beliefs and actions; where the householder/farmer and

the land represents the oppressive status quo; where the “enemy” is actually

good; and the “weed” represents the secret, mysterious, and the intertwining

nature of the gospel that is found in the subsequent two parables.

The point of

all this is not to dismiss the traditional, allegorical interpretation, or to

declare that the alternate interpretation is better. Rather, I offer it to suggest

a way to break out of years of prior hearing, experience, and tradition; to challenge

our assumptions, and to hear parables as they were originally meant to be heard

– to raise questions, to challenge beliefs, and to disquiet and discomfort its hearers.[6]

If parables only serve to confirm our beliefs and settle us, perhaps we have

not read them sufficiently well. If what I learned this week and offered to you

today provokes and challenges us, then I think the parable has done what it is

meant to do.[7]

[1]

Feasting on the Gospels: Matthew, Volume 1. WJK Press. “Exegetical

Perspective” and “Homiletical Perspective” on Matthew 13:24-30.

[2]

Wheat's

Evil Twin Has Been Intoxicating Humans For Centuries - Gastro Obscura

(atlasobscura.com) – https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/wheats-evil-twin-has-been-intoxicating-humans-for-centuries

[3]

Ibid.

[4]

Feasting on the Gospels: Matthew, Volume 1, p. 1009.

[5]

Ibid., p. 1015.

[6]

The back page of the Petersburg Lutheran Church bulletin for July 23, 2023 includes

yet another way of interpreting the parable of the weeds. See 07.23.2023-bulletin.pdf

(petersburglutheran.com) (https://www.petersburglutheran.com/hp_wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/07.23.2023-bulletin.pdf)

[7]

For an extended discussion of these ideas, see the “introduction” in Short

Stories by Jesus: The Enigmatic Parables of a Controversial Rabbi, by Amy-Jill

Levine.

No comments:

Post a Comment